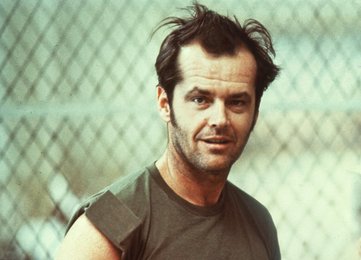

Nicholson at the Oscars: 1981 ("Reds")

From 1969 to 1975, Jack Nicholson garnered five Oscar nods, only missing out on recognition in 1971 and 1972. Remarkably, over the six years following his victory for One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, Nicholson would not once surface on Oscar nominations morning.

To say Nicholson's filmography on the heels of Cuckoo's Nest was a mixed bag would be an understatement. The latter half of the 1970s found the actor largely missing in action from the silver screen. The few pictures Nicholson did grace were ambitious failures.

In 1976, Nicholson took on two projects with legendary directors - Arthur Penn's The Missouri Breaks and Elia Kazan's The Last Tycoon.

The Penn picture was plagued by a troubled production, with protests by the American Human Association over alleged horse mistreatment on the set and fellow leading man Marlon Brando driving all participants bananas. The western, despite its star wattage, was a resounding box office flop and, not long after the film's release, Nicholson ended up suing the film's producers over unpaid wages. The Missouri Breaks is decidedly not a celebrated film among fans of Nicholson's nor Brando's.

The Last Tycoon, Kazan's final feature film, also failed to resonate among audiences or critics. This project, however, found Nicholson in merely a supporting role, taking a backseat to headliner Robert De Niro.

Nicholson spent much of 1977 preparing for his second directorial effort, of all things another western. Goin' South, ultimately released in the fall of 1978, sported one hell of a cast, including John Belushi, Christopher Lloyd, Mary Steenburgen and Danny DeVito, plus Nicholson himself in the lead, but proved polarizing among critics and too offbeat for a mainstream audience. It came and went from theaters in no time.

At last, in 1980, Nicholson found a project worthy of his talents.

Stanley Kubrick's The Shining, while now widely regarded as one of the all-time great horror films, was actually greeted to a lukewarm critical response upon release in the summer of 1980. The film opened to merely decent box office receipts but maintained strong legs over the season, eventually reaping twice its budget domestically. It was not until the expansion of cable and rise of video stores that The Shining really took off and built the legacy it sports today.

In the spring of 1981, Nicholson followed up The Shining with another dark turn, this time in old pal Bob Rafelson's remake of The Postman Always Rings Twice. The film's steamy romance between Nicholson and leading lady Jessica Lange generated ample chatter in the lead-up to its release but, largely on account of poor reviews, the picture merely broke even at the box office.

Nicholson's other 1981 release hardly had 'surefire hit' written all over it.

Warren Beatty had spent nearly 20 years trying to get a motion picture about Russian Revolution journalist John Reed off the ground. By 1979, Beatty at last had enough pull in the industry to send Reds into production and, in November of 1981, more than two years since the start of filming and at this point sporting a mammoth $32 million budget, post-production was finally complete.

At a time when ambitious, big-budget failures were leaving the likes of Martin Scorsese (New York, New York), Steven Spielberg (1941), William Friedkin (Sorcerer), Peter Bogdanovich (At Long Last Love) and Michael Cimino (Heaven's Gate) wounded, Beatty's Reds was quite the gamble.

That December, Reds hit theaters to rave reviews and respectable box office receipts, a relief for Beatty, his co-stars (Nicholson and Diane Keaton) and Paramount Pictures. Oscar nomination #6 was at last on its way...

The 1981 Oscar nominees in Best Supporting Actor were...

James Coco, Only When I Laugh

Coco portrays Jimmy Perrino, struggling stage actor and best friend of Georgia (Oscar nominee Marsha Mason), a recovering alcoholic who has returned home after a stint in rehab. Jimmy is determined to keep life low-drama for Georgia as she avoids the bottle but his own personal troubles, including his firing from a play mere days before opening, makes this a tough task. This performance marked Coco's first and final Oscar nomination.

John Gielgud, Arthur

Gielgud portrays Hobson, longtime butler of New York City playboy Arthur (Oscar nominee Dudley Moore). The sharp-witted Hobson, who has been more a father figure to Arthur than Arthur's own dad, plays matchmaker when Arthur shares his feelings for Linda (Liza Minnelli), a working class waitress who the family would hardly approve of. This performance, which won him honors from the Los Angeles Film Critics Association and New York Film Critics Circle, plus a Golden Globe, marked Gielgud's second and final Oscar nomination and first win.

Ian Holm, Chariots of Fire

Holm portrays Sam Mussabini, the renowned running coach who leads Cambridge University student Harold Abrahams (Ben Cross) to glory at the 1924 Olympic Games in Paris. Mussabini's involvement draws the ire of the snobbish (and anti-Semitic) Cambridge faculty, who criticize Abrahams for employing a professional trainer. This performance, which won him a BAFTA Award, marked Holm's first (and to date, final) Oscar nomination.

Jack Nicholson, Reds

Nicholson portrays Eugene O'Neill, the sad and cynical playwright who in 1916 befriends Louise Bryant (Oscar nominee Diane Keaton), an aspiring journalist who recently fled her life as a bored, married socialite. While colleague John Reed (Warren Beatty, who won an Oscar for directing the film) is away covering the Democratic Convention, O'Neill and Bryant become romantically involved. This performance, which won him honors from the National Board of Review and a BAFTA Award, marked Nicholson's sixth Oscar nomination.

Howard E. Rollins, Jr., Ragtime

Rollins portrays Coalhouse Walker, Jr., an African-American pianist who, after finding fame and fortune in a Harlem jazz band, travels upstate to be with his son and lover (Debbie Allen). Determined to marry the mother of his child, Coalhouse's quest is interrupted by racist local whites, inflamed that a black man could have such wealth and confidence. Coalhouse's vehicle is vandalized, drawing the pianist into a confrontation with law enforcement. This performance marked Rollins' first and final Oscar nomination.

Overlooked: Len Cariou, The Four Seasons; Richard Crenna, Body Heat; Griffin Dunne, An American Werewolf in London; Denholm Elliott, Raiders of the Lost Ark; Edward Herrmann, Reds; John Lithgow, Blow Out; Richard Mulligan, S.O.B.; Jerry Orbach, Prince of the City; Donald Pleasance, Escape from New York; Robert Preston, S.O.B.; Christopher Walken, Pennies from Heaven

Won: John Gielgud, Arthur

Should've won: James Coco, Only When I Laugh

Damn, there were a ton of marvelous supporting male performances in 1981. The Academy's selections are respectable for sure but just, if not more stellar would be a line-up of Dunne, Elliott, Lithgow, Preston and Walken. Not that the likes of An American Werewolf in London or Blow Out were ever winning major Oscar nominations, of course.

This category is a tough, tough call - for me, there's not that much of a dip in quality from my favorite to least favorite of the fivesome. In fact, over the years, I know I've flip-flopped among two or three contenders as to who I would've voted for.

All along, however, I believe it's been Rollins at the back of the pack. Frankly, this is less a knock on Rollins, a very good actor (who was also terrific in Norman Jewison's A Soldier's Story, later in the decade), and more about my qualms with his picture.

Ragtime should've been one hell of a movie. The 1975 E.L. Doctorow novel is deliriously great, Milos Forman had just done Cuckoo's Nest and Hair and the ensemble, on paper at least, is downright salivating. Ultimately, however, the proceedings are too stylized and move like molasses - its two and a half hours feel more like three and a half. Elizabeth McGovern, who was so warm and wonderful in Ordinary People the year prior, is woefully miscast in the pivotal role of Evelyn Nesbit and James Cagney, in his first screen turn in two decades (and his final film role), looks bored and is underused as the New York police commissioner. Imagine if Robert Altman tackled this thing!

Aside from the production design and costumes, where the bulk of energies went on the film, Rollins is one of the better parts of Ragtime and, in a picture packed with nondescript characters, for sure gives the most memorable performance. There's a liveliness to his screen presence that brightens up much of the film early on and his rage later in the picture is plenty palpable. He also, for what it's worth, has the most screen time of the five nominees.

That said, is Rollins strong enough to make the exhausting endeavor that is Ragtime worthwhile? I'm not so sure. It's a fine feature film debut but it's also a performance that sadly gets a little lost in the picture's chaos.

A whole lot more satisfying a picture is Chariots of Fire, a film I actually very much support in Best Picture. The Vangelis score is deservedly legendary, David Watkins' cinematography is sublime and director Hugh Hudson, who inexplicably never made another great film after this, paces the proceedings just beautifully.

Holm, always a delight to watch (he should've won an Oscar for 1997's The Sweet Hereafter), isn't a huge presence in Chariots but, when he does grace the screen, he steals scenes with effortless precision. His portrayal of Mussabini is a pugnacious one - think Burgess Meredith in Rocky, albeit a little less overbearing - but Holm also has some immensely heartfelt moments toward the film's end, as Mussabini is just as overwhelmed as his student by the glory of victory. It's a strong supporting turn in a film too often cast aside in the echelon of Best Picture winners.

I've long viewed Reds as more a triumph in filmmaking and authenticity than the most powerful of acting showcases. My favorite part of the film, by far, is Vittorio Storaro's sumptuous cinematography and the costumes and set direction are aces too. With that said, while I'm most struck by Beatty's meticulous attention to detail in nailing the look and feel of the period, the performances are plenty commendable and I'm very much taken with the Nicholson scenes.

This is for sure one of the more subdued Nicholson turns. He convincingly captures O'Neill's brilliance and and unhappiness, without much of that usual Nicholson persona bubbling to the surface. You can feel O'Neill's inner turmoil, both the joy and pain he feels in romancing a woman who's taken. Like Rollins, Nicholson's performance ultimately gets a little swept away in such a lengthy, epic picture but it's still a very notable turn and frankly, among the last occasions in which the actor really disappeared into a role.

Here's where I find myself see-sawing between who should've prevailed. It's a bit of a head vs. heart conundrum.

My head says Gielgud's long overdue victory was richly deserved. Despite everything fabulous about Arthur (which is a lot), this thespian on many an occasion threatens to walk away with the entire picture. Not only is this an outrageously funny performance (also, of course, credit Steve Gordon's top-notch screenplay) but toward the film's end, Gielgud does a complete 180 and completely breaks your heart. It's a brilliant turn from a juggernaut of the stage and screen.

My heart, however, is with Coco, irresistibly sweet, sad and funny in Only When I Laugh, the best and most underappreciated Neil Simon movie. The film is the closest Simon ever came to matching the quality of Woody Allen. It's an insightful, plenty entertaining 'neurotic New Yorkers' dramedy with a quartet of fabulous performances from Coco, Mason, Joan Hackett and Kristy McNichol.

Coco's Jimmy is a jubilant presence in the film, so delightfully effervescent he all but pops off the screen. We could all only hope for a best friend as awesome and supportive as Jimmy.

Somehow, Coco's performance sports the notoriety of being one of two performances (the other is Amy Irving in Yentl) nominated for both Oscars and Razzie Awards. I find it downright unfathomable that Coco could be considered a 'Worst Supporting Actor' for his wonderful work here and frankly, have always had a rotten feeling it had something to do with his portrayal of an openly gay character. These were, after all, the same Razzies that "awarded" the incredible likes of Dressed to Kill and Cruising around this time.

Anyway, it's a very close call between Gielgud and Coco - and the other three are quite fine too - but my passion is just a tad more with the latter.

The performances ranked (thus far)...

- Jack Nicholson, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest

- Al Pacino, The Godfather Part II

- George C. Scott, Patton

- Jack Nicholson, Five Easy Pieces

- James Earl Jones, The Great White Hope

- Al Pacino, Serpico

- Jack Nicholson, The Last Detail

- Al Pacino, Dog Day Afternoon

- Jack Nicholson, Chinatown

- Melvyn Douglas, I Never Sang for My Father

- Dustin Hoffman, Lenny

- Gig Young, They Shoot Horses, Don't They?

- James Whitmore, Give 'em Hell, Harry!

- James Coco, Only When I Laugh

- Jack Nicholson, Easy Rider

- Marlon Brando, Last Tango in Paris

- John Gielgud, Arthur

- Ryan O'Neal, Love Story

- Jack Nicholson, Reds

- Walter Matthau, The Sunshine Boys

- Ian Holm, Chariots of Fire

- Jack Lemmon, Save the Tiger

- Elliott Gould, Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice

- Howard E. Rollins, Jr., Ragtime

- Art Carney, Harry and Tonto

- Robert Redford, The Sting

- Albert Finney, Murder on the Orient Express

- Rupert Crosse, The Reivers

- Anthony Quayle, Anne of the Thousand Days

- Maximilian Schell, The Man in the Glass Booth